Jingjiang Princes’ Palace

- Shannon

- May 30, 2025

- 5 min read

The Jingjiang Princes’ Palace, constructed in 1372 during the early Ming Dynasty, served as the residence of Zhu Shouqian, a nephew of the dynasty’s founding Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang. Perched at the foot of Duxiu Hill in Guilin, the palace was more than just a lavish estate, it embodied the Ming strategy of installing Vassal Kings across the Empire to maintain dynastic stability and guard the frontiers. These vassal Princes, Imperial relatives granted nominal rule over regional territories, were intended to serve as bulwarks of loyalty. But over time, the court in Beijing grew increasingly suspicious of their power. The Jingjiang line, though geographically distant from the capital, remained under constant surveillance. Over 257 years, 14 generations of princes lived within the palace walls, each subject to strict protocols and imperial mandates meant to curb any potential rebellion. The grandeur of their station was matched by the ever-present weight of mistrust from the throne.

This paranoia wasn’t without cause. The Ming Dynasty experienced several internal conflicts involving imperial princes, such as the Rebellion of the Prince of Anhua in 1510, which heightened the court’s suspicion of regional princes. Across the empire, many princes were accused of plotting against the emperor, leading to harsh punishments. In the Jingjiang lineage, some princes reportedly met grim ends, executed or forced to commit suicide under charges of treason during the mid-to-late Ming period, particularly under the reigns of the sadistic Jiajing Emperor (1521–1567) and the reclusive Wanli Emperor (1572–1620), when court purges intensified. The imperial court’s fear of rebellion fostered a strict system of surveillance, with secret investigations and informants constantly monitoring the vassal kings. Consequently, the Jingjiang Princes’ Palace became not only a royal residence but also a place marked by political distrust, intrigue and purges aimed at securing imperial authority.

The construction of the palace itself was a brutal undertaking. Thousands of workers, including convicts and conscripted labourers, were forced to build the sprawling complex, which covered 19 hectares. Oral traditions claim that human sacrifices were offered to sanctify the land and ensure favourable feng shui, a common belief in imperial China at the time. While not officially documented, locals still tell tales of bodies buried beneath the foundations, believed to protect the palace from spiritual harm.

Throughout its history, the palace has been destroyed and rebuilt multiple times. It was damaged during the Qing conquest of Ming loyalist regions and later suffered further destruction in conflicts such as the bloody Taiping Rebellion and the Second Sino-Japanese War, when Guilin was bombed by Japanese forces. During these periods, the palace’s halls were used for military purposes, sometimes as barracks, sometimes as execution sites for dissidents and prisoners of war.

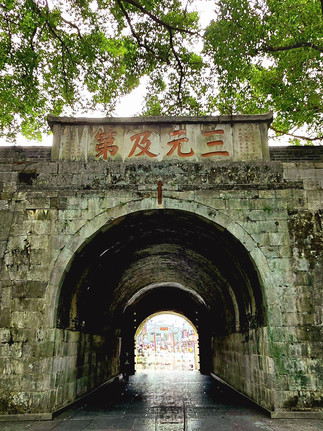

One of the darkest chapters came during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960's. Seen as a relic of “feudal” history, the palace was ransacked by the Red Guards. Ancestral tablets were smashed, priceless artefacts destroyed and ancient structures defaced. The shrine to the Prince’s ancestors, once the spiritual heart of the palace, was desecrated. What remains today is a restored version of the original, pieced together in the late 20th century through government led preservation efforts. While much of the palace has been rebuilt, a few original structures survived, including the Chengyun Gate, which is now over 650 years old, along with parts of the inner palace walls and sections of the stone foundations. Some of the cave and cliff inscriptions on Duxiu Hill also remain intact, offering rare physical links to the site's earlier history. These surviving elements provide valuable insight into the architectural style and cultural practices of the Ming period.

Behind the walls of the Jingjiang Princes’ Palace in Guilin, Duxiu Hill rises as a silent witness to centuries of imperial power and spiritual reflection. Carved into its limestone cliffs are over 800 inscriptions, dating from the Tang to the Qing dynasty, earning it the name “stone library of Chinese calligraphy.” During the Ming era, the vassal kings commissioned many of these carvings to declare loyalty to the Emperor and assert their legitimacy. Some inscriptions promote Confucian ideals, while others carry cryptic, sorrowful tones, believed by some to be the last words of condemned officials.

Hidden deeper in the rock are Daoist talismans and Buddhist sutras, suggesting the site was also used for ritual meditation and spiritual practice. The presence of a carved Taiji diagram hints at the mountain’s importance in feng shui, anchoring the palace’s energy. In later centuries, scholars journeyed here to carve poems before taking the imperial exams, seeking both inspiration and favour from the divine. Together, these inscriptions form a haunting and layered record of political ambition, spiritual longing and human fragility etched into stone.

Today, the Jingjiang Princes’ Palace is used as a cultural site and is part of the campus of Guangxi Normal University. It is open to the public and serves educational and tourism purposes. The site includes historical architecture, restored buildings, and preserved inscriptions. University activities take place within parts of the palace grounds. Visitors can access specific areas for sightseeing and learning about Ming-era history. The palace is also used for official cultural events and heritage preservation. Local traditions continue to associate the site with legends and ancestral rituals. It remains a significant location for historical research and tourism in Guilin.

Location : 1 Wangcheng Road, Xiufeng District, Guilin City, China

How to get there : To get from the Sun and Moon Pagodas to the Palace, you can walk about 1.5km's in roughly 20 minutes by heading west along Zhongshan Road through Zhongshan Park and Guilin Central Square until you reach the palace’s Chengyun Gate. Alternatively, you can take several public buses, including lines 2, 5, 16, 23, 88, or 208, getting off near Wenming Road and walking a short distance to the palace. A taxi or ride hailing service is also convenient, typically costing ¥10 - ¥15 and taking 5 - 10 minutes depending on traffic. Walking is the easiest option.

Attraction Info : the Jingjiang Princes’ Palace is open daily with varying hours depending on the season: from March 1st to April 30th, it operates between 7:30am - 6pm, from May 1st to October 7th between 8am - 6:30pm, from October 8th to December 7th between 7:30am to 6pm and from December 8th to February 28th between 8am to 6pm. Admission costs an unusually high ¥100 for adults, while children under 1.2 meters and students, faculty and staff of Guangxi Normal University can enter for free. Tickets can be purchased at the gate and you will need your passport. The palace complex includes several notable attractions such as Solitary Beauty Peak, Wangfu, Gongyuan, Crescent Lake and the Cliff Stone Carvings, making it a prominent cultural and historical site in Guilin.

靖江王府

Official Website : www.glwangcheng.com

Thanks for reading about Jingjiang Princes’ Palace. Check out more destinations here!